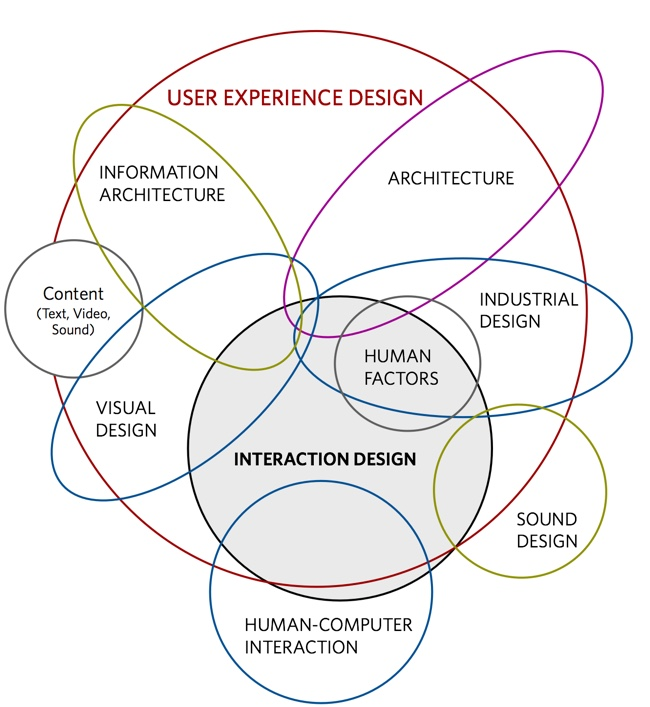

Overlapping and Evolving Titles of UX

The scope of responsibility in Product or/and UX design is so broad that, even today, many designers and companies still struggle to define what truly falls under these roles.

Companies Define What They Need—Or Do They?

Each company shapes the role of a designer based on their interpretation, but often not based on actual needs. Some add extra responsibilities, thinking, “If we’re hiring, let’s have them do X, Y, and Z too.” This often results in job expectations that go far beyond what’s realistic—or relevant to the role.

To make things even more confusing, job titles overlap—UX Designer, Product Designer, UI/UX Designer, and Product Experience Designer.

Some titles are used just in case, while the responsibilities actually require something different. The most common examples:

- “UX/UI Designer”, “UX Designer” or "Product Designer" → Sometimes, it’s actually just a UI design role.

- “UX Researcher” → But the role requires quantitative data analysis, SQL, and statistical modeling—essentially a Data Scientist.

- “Graphic Designer” → But the company expects branding, Printing Design UI, UX, and research.

Titles can vary significantly across companies, even when the responsibilities are the same. For example, a Product Designer at one company might focus heavily on UI, while at another, the role includes UX research, testing, and strategy. Additionally, even within the same company, expectations for a given title can differ based on an individual’s knowledge and skill set.

And I don’t even want to get into seniority levels—because in one company, a Senior Designer might be doing work that, in another company, is considered Junior-level.

Titles Don’t Always Match Responsibilities

Every company is at a different stage in its lifecycle. They hire designers based on immediate need, yet they still pack job descriptions with everything possible—companies often expect more than is actually needed.

This leads to:

- Overloaded Job Descriptions where designers are expected to do everything, sometimes even front-end development.

- Unrealistic Expectations. In many cases, only about 30%-50% of the listed skills are actually required for daily work, while the rest are either ‘nice-to-have’ or rarely used.

- Flooded applications—over 60% of job seekers apply even if they meet only part of the listed requirements.

- Role Blending—expectation in an all-in-one expert, but no designer can realistically cover everything.

Have you ever started a job where the role turned out to be nothing like the job description?

While inflated job descriptions happen in many IT roles, UX tends to suffer more from role blending—expecting one person to handle UX, UI, research, and sometimes even development.

This is happening because of UX still has overlapping and evolving titles & misunderstanding of a scope — people don’t fully understand UX and assume one person does it all, rather than recognizing the differences.

Defining Our Own Roles: The Challenge

As design professionals, we also need to be more transparent about what we actually do and what skills we bring to the table. And that’s the hard part. The field is so broad that even designers themselves struggle to define their focus areas.

- Where do we start?

- What should we learn first?

- What will actually be useful?

Understanding UX Disciplines

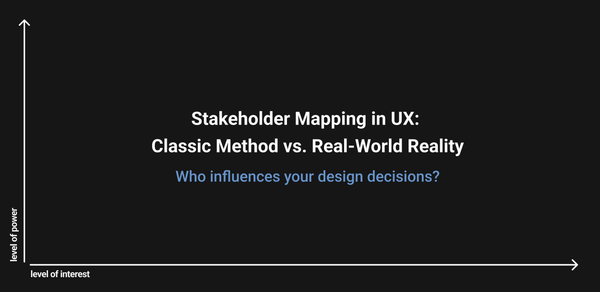

UX design is a broad field, covering multiple disciplines, from research to interaction design. The diagram below illustrates the various areas of UX:

Different Stages = Different Needs

Every company operates at different stages, and their design needs change accordingly:

- Discovery Stage – Focuses on qualitative research, understanding the problem space, asking the right questions, and defining what needs to be built.

- Validation Stage – Shifts toward quantitative data, measuring what works, analyzing impact, and refining based on evidence.

No one can be great at everything! Designers have different strengths, and that’s okay!

And just because one person excels at one skill set doesn’t mean that another designer, who works differently, is less skilled—they just have a different stack of strengths.

Skill Sets Over Comparisons

I’ve often been compared to other designers, and early in my career, I used to do the same—thinking in simple terms like, “I can do this, but another designer can’t.”

But over time, I realized that’s the wrong way to think.

It’s not about being better or worse—it’s about having different skill sets that align with different needs.

For example, I excel in discovery, so I thrive in early-stage development (0-1) or MVP. But if I were compared to someone who excels in validation and quantitative research, they’d outperform me in a later-stage company—even if they have less experience than me.

Instead of comparing designers as individuals, it makes more sense to compare their skills in relation to a company’s needs at that particular stage.

- So why do we still compare designers as if one is better than another?

- Why aren’t we comparing skill sets, methodologies, and how well they align with a company’s current needs?

- How can companies better define the skills they actually need before hiring designers?

- Why is there still so much misunderstanding and misalignment around what a designer actually does?

Unclear Responsibilities = Unrealistic Expectations

When roles are unclear, the designers still have to handle tasks outside of their “expected” responsibilities simply because they are necessary to achieve results.

It’s impossible to create something without understanding the context, the problem, and the needs—and that process takes time.

If the necessary information isn’t provided, the designer will step up and fill the gaps—because it’s impossible to design with closed eyes.

And if no one else is doing it, you’ll end up doing it anyway—even if it wasn’t explicitly asked.

Maybe that’s why companies increasingly prefer designers with experience in the same industry—because the expectation is to jump into the tools and “draw”, skipping the necessary discovery and strategy work.

The Industry Needs to Focus on Skills, Not Titles

As for me, instead of focusing on job titles, both designers and companies should should focus on specific skills and methodologies:

- Job descriptions should list what the designer will actually do rather than an overwhelming list of possible skills. It need to be based on actual project needs, not an inflated skill list.

- Designers should be clear about what they specialize in rather than trying to fit unrealistic descriptions and emphasize their unique skills and push back against unrealistic expectations.

Different Specializations

Take software development, for example to compare with different roles:

- Someone might be a Backend Developer, but their tech stack varies. One might specialize in PHP, another in JavaScript, and another in Python.

- No one expects a Backend Developer to know every backend language just because of the title.

- I’ve never seen a company to hire a PHP developer, expect them to work in a different language, and then claim they’re not a good developer.

Breaking the Cycle

In product design, companies sometimes seek designers who can handle a wide range of responsibilities. However, this can lead to unrealistic expectations when no single person can truly excel in every area.

It’s time to break this cycle. Instead of chasing inflated job descriptions, let’s focus on defining clear responsibilities and right skills.

The conclusion

By having clearer descriptions, aligning skill sets with company current needs, and fostering better communication, we can create a more effective and sustainable process for both designers and businesses.

Let’s work together to shape a future where design roles are well-defined, valued, and aligned with real business challenges.